During an interview for the UK'S The 100 Greatest Scary Moments, Shelley Duvall revealed that due to her role requiring her to be in an almost constant state of hysteria, she eventually ran out of tears from crying so hard. To overcome this she kept bottles of water with her at all times on set to remain hydrated.

Stanley Kubrick had envisioned Shelley Duvall as his more timid, dependent version of Wendy Torrance from the very beginning. However Jack Nicholson after reading the novel, wanted Jessica Lange for the part of Wendy, and even recommended her to Kubrick, as he felt she fit Stephen King's version of the character. After explaining the changes he had made, Kubrick convinced him that Duvall was the correct choice, as she best suited the emotionally fragile Wendy he had in mind. Many years later, Nicholson told EMPIRE magazine he thought Duvall was fantastic and called her work in the film, "the toughest job that any actor that I've seen had."

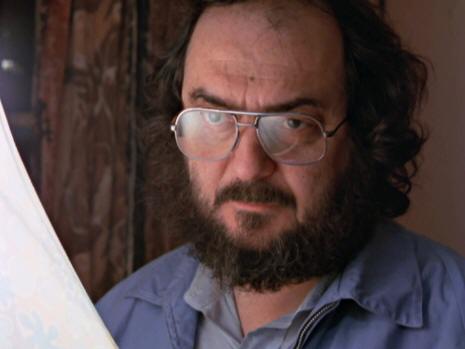

Despite Stanley Kubrick's fierce demands on everyone, Jack Nicholson admitted to having a good working relationship with him. It was with Shelley Duvall that he was a completely different director. He allegedly picked on her more than anyone else, as seen in the documentaries Making 'The Shining' and Stanley Kubrick: A Life in Pictures. He would really lose his temper with her, even going so far as to say that she was wasting the time of everyone on the set. She later reflected that he was probably pushing her to her limits to get the best out of her, and that she wouldn't trade the experience for anything - but it was not something she ever wished to repeat.

Apparently, Stanley Kubrick was so displeased with Shelley Duvall casting for the role of Wendy Torrance that he deliberately mistreated her on set in order to get her to better portray the emotionally shattered spouse.

On the DVD commentary track for Making 'The Shining', Vivian Kubrick reveals that Shelley Duvall received "no sympathy at all" from anyone on the set. This was apparently Stanley Kubrick's tactic in making her feel utterly hopeless. This is most evident in the documentary when he tells Vivian, "Don't sympathize with Shelley." Kubrick then goes on to tell Duvall, "It doesn't help you."

This would drive me crazy. But that was his intention, right?

Karina began her career as a model for Chanel before deciding to try films. "Jean-Luc asked me to play a small part in Breathless, the role of Belmondo's former girlfriend. It was just one scene. I asked him what I had to do and he said, 'You have to take your clothes off,' and I said no. I thought that was that, but a few months later, he asked me to come in again, telling me, 'This time it's a lead.' So I said, 'Do I have to take my clothes off?' He said, 'No, it's a political film.' "

That film was Le Petit Soldat, Godard's thriller about the Algerian war, which in one pivotal scene features the "enhanced interrogation technique" we know today as waterboarding. "I told him I know nothing about politics, and he said, 'Don't worry about it. You just do what I tell you to do. Come in and sign your contract.' I was underage so I had to get my mother to sign it for me. And then we started, and that was the beginning of the whole story."

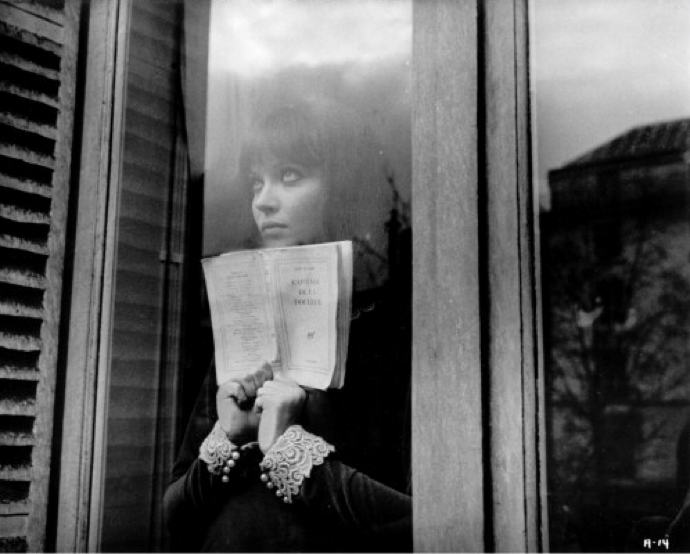

The "story" eventually encompassed a wide range of cinematic experiments, from the lightweight musical A Woman Is a Woman to the heavyweight study of prostitution Vivre Sa Vie and the quirky crime thriller Band of Outsiders. All of them were keyed to Karina's face and body, with special attention paid to the soulfulness of her enormous eyes, frequently staring straight into the camera — at Godard, at us.

It's fitting that in their final collaboration, Made in USA, Godard cast Karina as a "woman of action" — a character who, in the novel that is the film's source, is in fact male. That's because, for Godard, Karina was never an actress like all the others; she was in some ways a kind of female version of himself.

Karina's mother was a dress shop owner and her father was a ship's captain who left the family a year after she was born. She lived with her maternal grandparents for three years, until she was four. She spent the next four years in foster care when she returned to live with her mother. She has described her childhood as "terribly wanting to be loved", and as a child made numerous attempts to run away from home.

If anyone is an authority on "how it was" to be with Jean-Luc Godard at the height of his fame in the 1960s, it's Karina. The muse-cum–leading lady of eight of the fabled writer-director's most important films, and his offscreen spouse from 1961 to 1967, Karina was more than merely "there." On-screen and off, Godard and Karina were in such emotional and intellectual rapport, he had only to glance at her to get the result he sought. "All these movies were presents from Jean-Luc to me," says the actress on the phone from Paris."

That an ex-wife should harbor no residual bitterness toward a former spouse may be unusual. But if you're familiar with the films they made (including A Woman Is a Woman,Vivre Sa Vie, Band of Outsiders andAlphaville), you'll know why. Whatever passed between Godard and Karina personally, professionally they were a powerful team, not casually tossed asunder. He offered her exceptional roles, and he needed her to enact his dramatically cinematic ideas. Godard felt all films were at heart documentaries; even in the midst of creating fictional characters and stories, he wanted every moment to be "felt" and true. And Karina was in complete agreement. It's not easy to find an actress who can stab a man to death and then sing a song as she ignores the corpse, as Karina does in Pierrot.

Their relationship was, as Cole Porter would say, "too hot not to cool down." Before that inevitable cooling, there were explosions, asJacques Rivette shows in his film à clef of the Godard-Karina breakup, L'Amour Fou, which climaxes with the principal couple (played by Bulle Ogier and Jean-Pierre Kalfon) locking themselves in their apartment for a romantic, emotional free-for-all. The films Godard and Karina made together, particularly Pierrot le Fou, reflect this heat, while along the way reworking just about every convention that had existed in cinema up to that point. Godard called the characters in Pierrot le Fou "the last romantic couple," with Belmondo representing "passive life" and Karina "active life." This perfectly encapsulates the Godard-Karina dynamic. She was "action" — he was the one who observed it.

"We didn't have a script, but with Jean-Luc we didn't really need one," Karina recalls of Pierrot le Fou (though she might just as well have been speaking of any of their collaborations). "It was like an understanding between us. He would say, 'Anna, a little bit quicker or a little bit slower.' That was all. We didn't do a lot of retakes. With some other actors I know he would do a lot of retakes, but not with me."

Godard seems decent and decisive and Anna Karina seems happy and willing.

Eh why not? Let's give it a go.