Run, Lolita, Run

NY X: “Jane Eyre” is rated PG-13 (Parents strongly cautioned).

Chaste passion, discreet violence.

What was that, NYT? What kind of passion? What kind of violence?

Much as Jane combines what would seem to be incompatible traits within a single voice and body — her employer and soul mate, Edward Rochester, is an even wilder brew of contradictions — so does Brontë’s “Jane Eyre” mash up genres and effects with mesmerizing virtuosity. The novel’s blend of Christian piety, Gothic horror, barely suppressed eroticism and high-toned comedy satisfied readerly appetites in the Victorian era and ever after. Brontë’s themes and moods — the modulations of terror and wit, the matter-of-fact recitation of events giving way to feverish breathlessness — are carefully preserved.

There is something voluptuous in the rage inspired by the kind of meanness we are used to calling Dickensian. The oppressors are so awful, the oppressed so innocent, that the desire to see justice done becomes an almost physical hunger. And as in Dickens, the brutality and dogmatic moral arrogance of Jane’s righteous oppressors at the Lowood school have a political dimension, one compounded by Brontë’s clearsighted feminism.

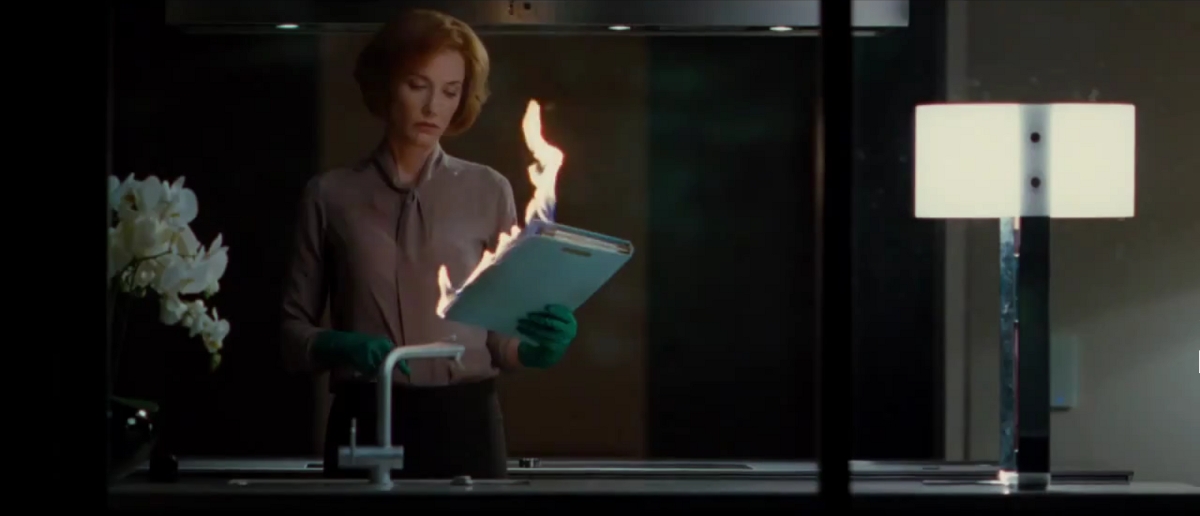

Ms. Buffini’s script, while it trims and winnows some of Brontë’s empurpled passages [RUDE], preserves important elements of the author’s language, including, above all, Jane’s repeated invocations of freedom as an ethical and personal ideal. Freedom in “Jane Eyre” is a complicated theme in its own right — on the Internet you can buy several term papers that explore it — and also a word whose value and meaning change over time. For the Jane in this movie, it means the ability to act without external constraint and to think without fear or hypocrisy.

Rochester may be an impossible character — dashing, wounded, cynical, wild and yet somehow redeemable — but for that very reason he is vital to both the wild romanticism and the sober good sense that have kept “Jane Eyre” spinning through so many generations and interpretations.

His Rochester, greyhound lean, with a crooked, cynical smile set in an angular jaw, is very plausibly a thinking girl’s half-inappropriate crush object. Mr. Fassbender adds to the necessary charisma and pathos a note of gallantry, helping to assure the audience and his indomitable co-star that this “Jane Eyre” belongs, as it should, to Jane.

Jane Eyre may lack fortune and good looks — she is famously “small and plain” as well as “poor and obscure” — but as the heroine of a novel, she has everything. Ms. Wasikowska, a lovely 21-year-old actress who fulfills the imperative of plainness with a tight-lipped frown, a creased brow and severely parted hair, is a perfect Jane for this film and its moment. She has already tackled another notable 19th-century literary heroine —Alice in Tim Burton’s weird renovation of “Alice in Wonderland”. Her Jane withstands strong crosswinds of feeling and the buffeting of unfair circumstances without self-pity, but also without saintly selflessness.

Can't tell who's who. Is it racist or racial to say that all white girls look more or less the same to me?